Weddell Sea Refugia Expedition

Adelie penguins on the western side of the Antarctic Peninsula have been in decline for years, in part due to the effects of anthropogenic global climate change. As the climate changes around South America and in other parts of the globe, warmer, wetter air can end up in Antarctica causing excess snow and rain, and warm water from deep in the ocean can creep up into Antarctic coastal waters, changing the dynamics of the ecosystem.

The Danger Islands

In 2015, our team surveyed the remote Danger Islands archipelago that sits at the northern edge of the Weddell Sea. There we found a massive and apparently thriving colony of Adelie penguins - more than a million of them. That expedition made us wonder if the rest of the Weddell Sea might similarly have been spared from the worst of the environmental change seen on the other side of the Antarctic Peninsula.

The expedition begins.

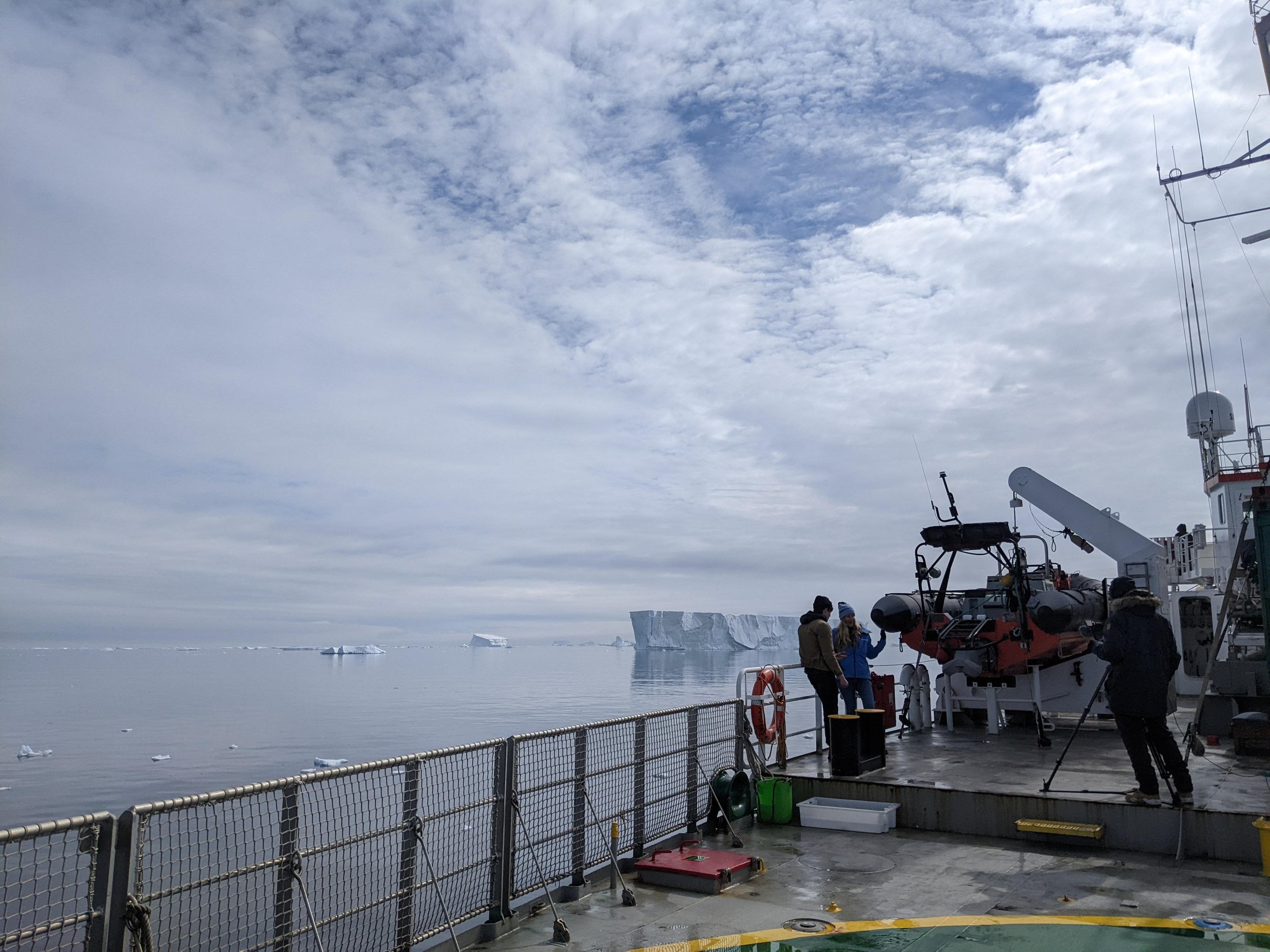

After our friends at Greenpeace approached us with interest in staging another Antarctic expedition, we saw an opportunity to answer our questions about Adelies in the Weddell Sea. After quarantining in Argentina, we boarded the Arctic Sunrise, their ice-class working ship, and headed south. Our first days, after crossing the Drake Passage, were slow. The Weddell Sea has a habit of making vast fields of sea ice that swirl and shift, blocking passage in unpredictable ways.

How we work

We’d previously conducted a satellite study of the region, looking for areas where bright-colored penguin guano shows up even from outer space. That gave us a general idea of where penguin colonies were, and how large they might be. We wanted to get clearer data, and to build 3D models to help us census the colonies and study the topography and snow-drainage dynamics of the colonies.

To do this, we used simple, commercial quadcopter drones. These UAVs fly in pre-programmed grids over a colony or island and capture overlapping images. We can stitch these photos together and use the difference between images to measure the terrain and create 3D maps.

A penguin census

More than a map, we want to know how many penguins there are, and compare that to any information we have about population size in the past (and create a point of comparison for the future. We do this in two ways: First, we do manual counts - tallying up each penguin nest or, when the chicks get big enough, each individual chick, to understand the population size. We count each of these 3 times and compare our counts to ensure accuracy.

Second, we can use the UAV imagery to either count manually back in the lab, or using machine learning methods, where we train a computer to count nests for us.

Antarctica is rarely cooperative. It’s a remote, extreme environment where sudden winds can make getting a boat ashore unsafe, and sea ice and massive icebergs can be drawn by currents and winds to block channels. We often spent hours or days looking for opportunities and waiting for conditions to clear.

In Antarctica it’s always worth having plans A through C prepared in advance, but even then we often found ourselves coming up with plan D, E, and F for the day.

But often, unexpected hardship, delays, and challenges are what lead to discovery. When ice blocked a massive channel to the Weddell Sea, we took a detour around the top of Joinville Island, and discovered several penguin colonies new to science, and a Gentoo penguin colony that had likely only been established in the last 10 years as Gentoos have expanded their range.

Gentoos are a more sub-Antarctic species, but their numbers are growing around the Peninsula as conditions have shifted.

One of the great joys of exploration is sharing it with other people, and reveling together in the experience of discovering new things, and working alongside one another in incredible, breathtaking, and challenging places